The era of resilience against diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, which began with the discovery of penicillin in 1928, has come to an end. Experts are warning that the rise of drug-resistant superbugs could make the COVID-19 pandemic seem trivial in comparison.

According to Sally Davies, the UK’s special envoy on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the growing number of untreatable infections could force societies to isolate individuals to prevent the spread of these deadly pathogens.

“It’s a truly disastrous scenario,” Davies said, sharing that her own goddaughter died two years ago from an infection that modern medicine could not treat. “Some aspects of COVID would seem minor in comparison,”

AMR is already responsible for 5 million deaths annually, and new research published in The Lancet on 16 September warns that drug-resistant superbugs could claim nearly 40 million lives by 2050.

This warning comes ahead of a critical meeting at the United Nations General Assembly on 26 September, where global leaders will discuss measures to combat AMR.

Key strategies are expected to include infection prevention, vaccinations, reducing antibiotic use in both agriculture and human medicine, and advancing research into new antibiotics.

Could a Simple Infection Become Fatal?

Experts are concerned that, without immediate action, even minor infections could become life-threatening. “Could you die from a simple dental infection? With AMR, this could become an everyday reality,” warned Lindsey Edwards, a microbiology expert at King’s College London.

In Africa, deaths from AMR already surpass those from malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis, according to a report from the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and the African Union’s InterAfrican Bureau for Animal Resources.

“If AMR spreads unchecked, many infectious diseases will become untreatable, erasing a century of medical progress,” the report said

War and the Spread of Resistant Infections

Conflicts, such as those in Gaza and Ukraine, present an additional threat. The combination of poor hygiene, heavy metals used in weaponry, and limited access to essential medicines creates a breeding ground for drug-resistant infections.

The World Health Organisation warns that these conflicts could lead to the spillover of resistant infections into neighboring regions, Europe, and the US.

However, there are concerns that industries like pharmaceuticals and agriculture will lobby to weaken the actions needed to address AMR.

An early draft of the UN resolution seen by Politico called for a 30% reduction in global antibiotic use in food production by 2030 and the elimination of antimicrobials essential for treating human infections in livestock.

While global cooperation is critical, achieving ambitious targets akin to those for climate change or HIV may be challenging in a time of reduced multilateral collaboration.

A more recent version of the UN resolution softened its stance, stating that countries should “strive to meaningfully reduce” antibiotic use in the food industry by 2030, and “commit to ensuring that antimicrobials in animals and agriculture are used prudently and responsibly.”

The final draft, dated 9 September and seen by Politico, showed little change in this approach. It set a target of reducing global deaths caused by bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) by 10% by 2030, based on the 2019 figure of 4.95 million deaths.

One of the proposed control measures is the establishment of a global independent panel on AMR, modeled after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Countries are beginning to pledge funding for this initiative, amid warnings that AMR could cost the global economy up to $100 trillion by 2050.

Low- and middle-income countries, which bear the brunt of AMR’s impact, are calling for increased investment in clean water, sanitation, infection control, and childhood vaccinations. These needs are growing while development budgets in wealthier nations are shrinking.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) issued new global guidelines on 3 September to tackle antibiotic pollution and pharmaceutical waste from manufacturing—currently, a largely unregulated area. However, it remains to be seen how widely these guidelines will be adopted.

In a related warning, the WHO also highlighted the emergence of a “hyper-virulent” drug-resistant superbug, Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKp). This dangerous strain has been detected in the US and 15 other countries.

Capable of causing deadly infections such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections, and meningitis, hvKp poses a threat even to individuals with healthy immune systems. Experts fear its prevalence may be underestimated.

The Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance

Imagine a world without antibiotics: a paper cut could be fatal, and routine surgeries, minor health issues, and childbirth would pose serious risks. This was our reality less than 100 years ago, and we may face it again due to rising antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

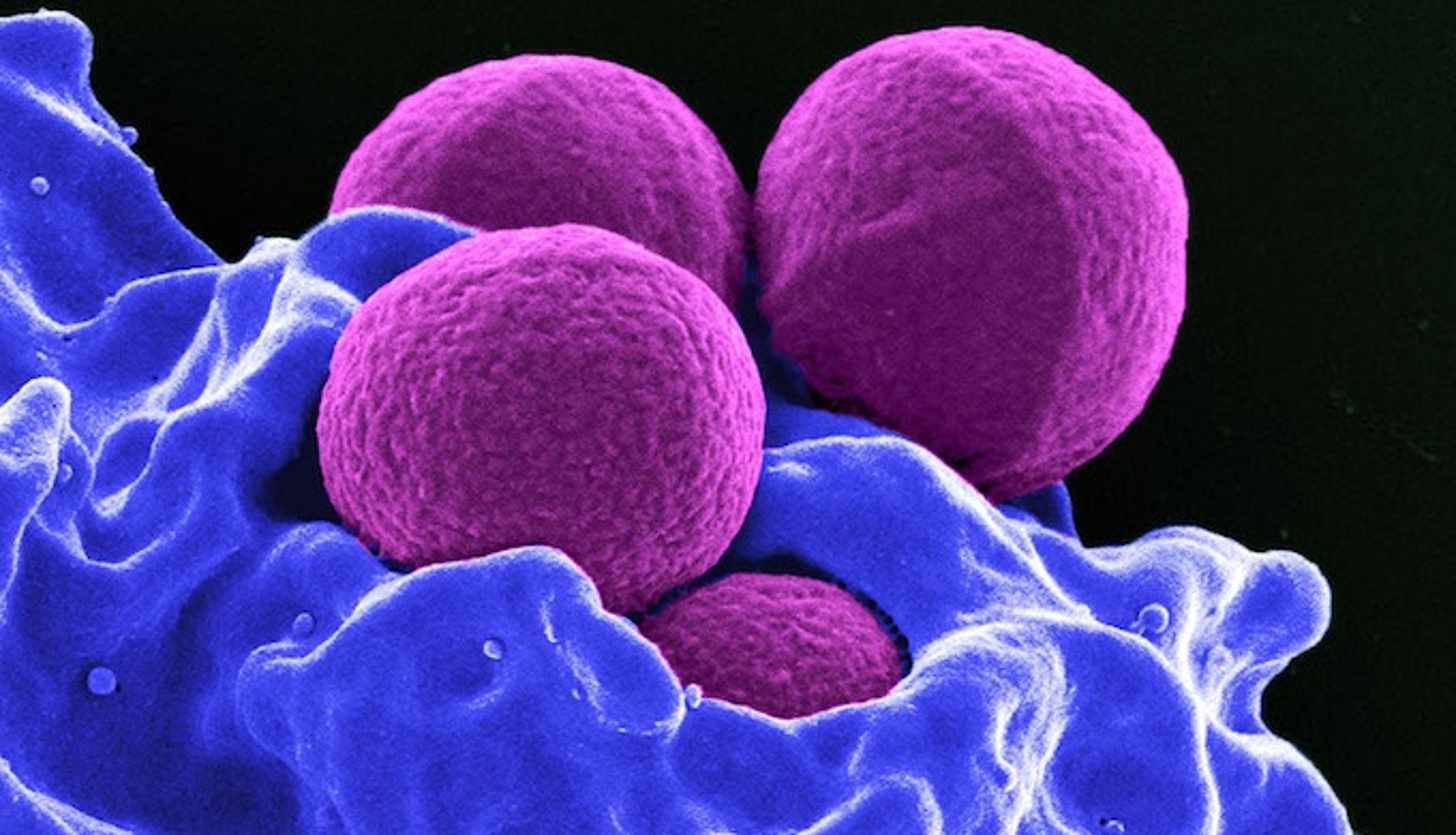

AMR occurs when bacteria become resistant to antibiotics, leading to ‘superbugs’ that can cause hard-to-treat, life-threatening infections. If unchecked, these superbugs could eliminate our ability to effectively treat infections and perform lifesaving surgeries.

As the global meeting in New York approaches, it remains to be seen whether these growing warnings will prompt world leaders to take stronger, decisive actions against the looming threat of AMR.