According to the Speedtest Global Index, Australia ranks 64th in the world for fixed broadband speeds making it the slowest internet connected developed country with an average download speed of 46.24 Mbps. New Zealand ranks slightly higher at 50th, with an average download speed of 73.87 Mbps

The Akamai State of the Internet Report says Australia’s internet connection speeds are now slower than 50 other nations, including Thailand, Estonia, Bulgaria and Kenya

Australia’s slow and expensive internet speeds result from many factors, including its vast geography, low population density, limited competition, outdated infrastructure, government policies, limited international connectivity, high costs, and technological challenges

Australia’s ambitious National Broadband Network (NBN) project was meant to address these issues but has faced delays and cost overruns. However, the shift to a fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) approach would seem to have failed to bring Australia up to speed in the global rankings for consumer level internet.

For Australians, it seems that the dream of fast and affordable internet remains elusive, especially when compared to their counterparts in the United States.

As the global digital transformation continues to reshape the way we work, study, and shop, the quality and accessibility of internet services is now playing a pivotal role for homes, businesses and the education sector.

Australia’s Internet Infrastructure Falls Short

While the United States boasts some of the world’s fastest internet speeds, Australia’s internet infrastructure often falls short of delivering similar performance. This has a significant impact on various aspects of daily life, from work productivity to the quality of online education and entertainment experiences.

Not only is Australian internet slower, but it is also often more expensive. When compared to their American counterparts, Australians pay a premium for their internet services.

As a result, the countries internet speed is currently leaving many consumers feeling shortchanged, particularly as internet access becomes an essential utility.

Oceania – Internet Speeds

Oceania, a geographical region encompassing the continent of Australia and numerous islands dotting the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, boasts a diverse tapestry of cultures, languages, and landscapes.

Its history is punctuated by exploration, colonisation, and struggles for independence, making it a region of historical significance. With a population exceeding 40 million, Oceania holds considerable economic, political, and social weight on the global stage.

Given the internet’s paramount importance in modern life, it becomes increasingly critical to scrutinise Oceania’s internet infrastructure, patterns of usage, and related policies in a global context.

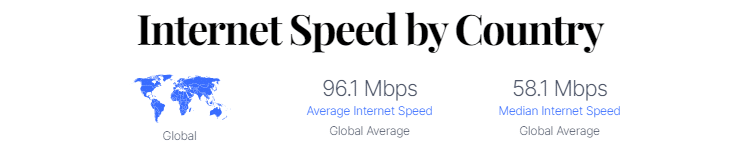

The average internet speed for Oceania, registers at a somewhat modest 50.67 Mbps, painting a picture of internet connectivity that, while functional, lags behind the blistering speeds experienced in other parts of the world.

- Australia and New Zealand – Undersea Cables

In the depths of the Pacific Ocean, a web of undersea cables silently weaves its intricate threads, serving as lifelines that bind Oceania to the pulsing heart of the global internet.

These cables, unseen by most, form the backbone of connectivity, uniting distant lands, including Australia, New Zealand, and other island nations, to the rest of the world.

With an almost mystical capability, these undersea cables bear the weight of immense data flows, carrying the digital dreams and necessities of businesses, governments, and individuals alike.

They are also the conduits of an interconnected world, enabling the swift and unwavering flow of information, transcending oceans, time zones, and borders.

Australia and New Zealand, like formidable guardians of this digital realm, stand as the primary gateways through which these undersea cables make their connection to Oceania.

Australia, a continent of vast expanses, boasts several landing points for international submarine cables, bearing names that resonate with power. The Australia-Japan Cable, the Southern Cross Cable, and the formidable SEA-ME-WE 3 cable.

New Zealand, although smaller in size, plays its part with unwavering dedication, serving as the custodian of two major undersea cables, the Southern Cross Cable and the Tasman Global Access Cable.

Yet, despite their valiant efforts, Oceania’s internet infrastructure remains shrouded in a veil of deficiency. In the grand theater of global internet rankings, Oceania finds itself playing a supporting role, lagging behind its counterparts in terms of speed, capacity, and affordability.

The reasons behind this digital disparity are as profound as they are disheartening. Oceania’s very geographical isolation, a testament to its remote existence, emerges as a formidable foe.

The vast, sprawling expanses of oceanic separation make laying and maintaining undersea cables a herculean task. These challenges inevitably translate into higher costs and agonising delays in the delivery of internet connectivity.

The complexity of Oceania’s intricate tapestry further complicates matters. A vast collection of small island nations, each with its own unique set of challenges, stands as a testament to the region’s diversity.

Limited resources and daunting logistical hurdles conspire to make investing in and sustaining internet infrastructure a formidable endeavor. Political instability also casts its shadow over some nations, rendering them less attractive to foreign investments, further deepening the digital divide.

Internet Usage in Oceania Surges Over The Past Decade

Over the past decade, the surge in internet usage across Oceania has been nothing short of meteoric, with over half of the region’s population now embracing the technology.

The remarkable growth can be attributed to the widespread availability of affordable smartphones and the expansion of internet infrastructure, making it effortlessly accessible to individuals from virtually anywhere.

Yet, when viewed through a global lens, Oceania’s internet adoption stands relatively modest, with roughly 60% of the populace being active users.

According to data from Internet World Stats, Oceania ranks fifth among the world’s six major regions in terms of internet penetration, surpassed only by Africa, where internet access remains even scarcer.

However, the landscape of internet utilization within Oceania is far from uniform. Across the region, usage rates vary significantly from one nation to another.

For instance, in Australia, a staggering 86% of the population harnesses the internet’s power, while in Papua New Guinea, a mere 12% of its inhabitants are connected.

Reflecting global trends, the most prevalent internet activities in Oceania align with those found in other regions. Social media platforms, video streaming, and online shopping reign supreme.

In countries like Australia and New Zealand, social media giants such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter hold court, acting as virtual town squares where people connect with loved ones, share content, and stay abreast of current events.

Additionally, the allure of on-demand video streaming services like Netflix, Stan, and Amazon Prime continues to captivate audiences, providing a cinematic escape at their fingertips.

The e-commerce wave has also washed over Oceania, with platforms like Amazon, eBay, and local retailers riding the digital tide as consumers increasingly opt for online shopping.

Beyond these entertainment and consumer-driven activities, the internet serves as an indispensable tool for education, healthcare, and communication across Oceania.

Online education platforms such as Coursera and edX democratise learning opportunities, enabling individuals in the region to access high-quality educational resources from the far corners of the globe.

In the realm of healthcare, the burgeoning popularity of telemedicine services empowers people to seek medical consultations and advice online, reducing geographical barriers and enhancing healthcare accessibility.

Factors Affecting Internet Speed In Australia

A primary factor influencing internet speed within Oceania stems from the region’s inherent remoteness. The presence of numerous small island nations poses formidable obstacles, rendering the installation and upkeep of internet infrastructure an arduous and costly endeavor.

Moreover, the considerable geographical gulf separating Oceania from major internet exchange points, typically nestled in North America and Europe, exacerbates matters by introducing extended latency periods and consequently, sluggish internet speeds.

In 2009, the Australian Labour Party introduced an ambitious policy aimed at implementing the cutting-edge FTTP (Fibre to the Premises) network, heralded as the pinnacle of internet service provision in terms of speed and efficiency.

However, a change in government following the 2013 federal elections shelved this policy. The Liberal Party, which assumed power, charted a different course and formulated its own vision for internet access, aptly named the MTM (Multi-Technological Mix) plan.

The new approach involved utilising existing copper cables in conjunction with a blend of newly introduced technologies like FTTN and FTTC, among others.

Regrettably, the government was unable to fulfill its commitment of delivering high-quality, cost-effective internet services as envisioned.

The initial budgetary projections of $29.5 billion proved grossly insufficient, with costs skyrocketing to over $70 billion, particularly after factoring in the upgrades to FTTP technology.

The adoption of this outdated FTTN approach, combined with a mixture of old and new infrastructure elements, has proven to be a regrettable decision from the outset. It has inflicted substantial damage on Australia’s overall budget and has been marred by persistent delays.

NBN program critic Mark Gregory, who also serves as an expert in telecommunications and network engineering at RMIT, contends that if the initial plan (the Labour Party’s proposal to implement FTTP technology directly) had been approved from the outset, the project would likely have incurred costs of approximately $50 billion upon completion.

Gregory also went on and characterised the current state of affairs as “Australia’s greatest infrastructure disaster.”

Many share this sentiment, especially considering that Australians continue to grapple with sluggish internet speeds, while those in remote regions often have no access to reliable internet services at all.

Dr. Tama Leaver, an associate professor specializing in internet studies at Curtin University, laments that the NBN should have embraced a comprehensive approach, delivering fiber connections to every home.

Such an approach would have not only facilitated remote work and seamless connectivity but also ensured full participation in the digital economy.

Instead, the NBN has become a patchwork of antiquated and modern components, with ultimate internet speeds hinging on the weakest links in the network—a far cry from the original vision of a robust, high-speed internet infrastructure.

Australia’s High-Cost Low Speed Internet.

The Australian telecommunications landscape is largely dominated by Telstra and Optus, with Telstra holding a prominent position as the primary owner of internet infrastructure.

The telco’s commanding presence in the market has translated into relatively high costs for those seeking premium internet services.

One of the catalysts behind the establishment of NBN Co. was the breakdown of negotiations between the government and Telstra regarding potential collaboration. However, it’s essential to note that even with the NBN’s FTTP (Fibre to the Premises) technology, cost-effectiveness was not a guaranteed outcome.

Consumers faced a stark choice – either shell out a hefty sum for blazing speeds of 100 Mbps or 1000 Mbps, or settle for subpar internet quality at more affordable rates.

Adding to consumer woes, 2021 witnessed a startling revelation as Telstra, TPG, and Optus engaged in deceptive practices. They said their respective NBN plans couldn’t realistically deliver the advertised internet speeds resulting in overcharging consumers and forcing them to pay a premium for speeds that the telco’s knew were unattainable.

Furthermore, these companies failed to disclose to their customers that they had the option to migrate to more economical plans while maintaining the same speeds.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) responded by initiating legal action against all three telecom behemoths. However, these companies offered explanations centered around the intricacies of the process and the assertion that internet speeds couldn’t be accurately determined until the NBN connection was established.

Whether these telcos imposed high costs unintentionally or deliberately, one undeniable reality remains – the absence of robust competition in the market has allowed these companies to become complacent, often neglecting the imperative to prioritise customer needs.

Australia’s Explanation For Slow Internet Speeds

The most common and logical explanation you’ll find out there is that Australia is a big continent but the population density is low. That means that there aren’t many people living on the continent, which makes the internet equipment more expensive and less cost-effective.

Some say, the explanation makes sense, as internet companies don’t have an incentive to invest in good equipment that will eventually be used by a small number of people and won’t pay off.

In 2019, RMIT University Associate Professor of Engineering Mark Gregory said, “There’s a big difference between an outcome that’s national and an outcome that might only cover 10% of a population in a country,” Gregory said.

He also added that despite the comparison being a difficult one, Australia is still not kicking any goals in the speed department.

“It’s a bit of comparing apples with oranges, but I would say that if you look at it in terms of the trend and the numbers of connections and what those connections are providing then you would have to say Australia is doing very poorly,” he said.

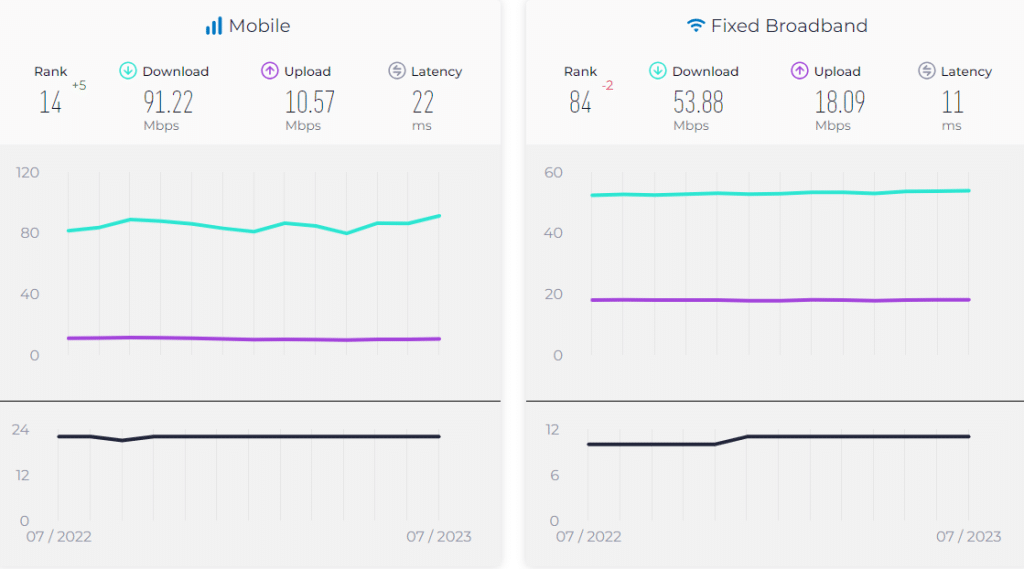

Australia Median Country Speeds July 2023

Speedtest Intelligence® reveals that among top mobile operators in Australia in Q4 2022, Telstra delivered the fastest median download speed at 96.16 Mbps.

- Median Multi-Server Latency

Australia’s mobile multi-server latency results in Q4 2022 showed that among top providers, Optus registered the lowest median multi-server latency in Australia at 34 ms.

Government Policies

In Australia, the government has implemented stringent regulations governing internet usage, particularly concerning online content. Oversight of online content falls under the purview of the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), acting through the Broadcasting Services Act.

The legislation mandates that internet service providers (ISPs) block access to websites housing illegal or harmful content.

Additionally, Australia has introduced data retention laws compelling ISPs to retain metadata for a duration of two years, aiding investigations into serious criminal activities.

In contrast, New Zealand’s approach to internet regulation takes a more hands-off stance, prioritizing the safeguarding of citizens’ privacy rights. Notably, the Privacy Act of 2020 mandates that companies obtain explicit consent from individuals before collecting and utilising their personal information.

Additionally, New Zealand has implemented laws aimed at combating cyberbullying and revenge porn, deeming such actions criminal offenses.

When compared to other global regions, Oceania’s government policies and regulations pertaining to the internet tend to emphasize concerns like online content management and cybersecurity.

In Europe, for instance, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been rolled out to safeguard individuals’ privacy rights, compelling companies to secure explicit consent before gathering and utilizing personal data.

Meanwhile, in China, the government has instituted rigorous censorship laws to supervise online content, and the Great Firewall of China bars access to numerous foreign websites and services.

Taken together, government policies and regulations governing the internet in Oceania reflect the region’s distinctive challenges and opportunities.

With a particular focus on issues like cybersecurity and the regulation of online content, regional governments strive to strike a delicate balance between preserving the advantages of an open and unrestricted internet and safeguarding the rights and safety of their citizens.

11 Years Past When The Australian Government Admits It Was Wrong About Broadband

Australia’s ambitious National Broadband Network (NBN) project was meant to address these issues but has faced delays and cost overruns. The shift from a fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) approach to a multi-technology mix (MTM) has also had implications for overall internet speeds.

On April 7, 2009, then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, alongside his Communications Minister, Stephen Conroy, heralded the commencement of a groundbreaking national broadband network strategy.

At the heart of this initiative lay a transformative technology – fiber to the premises (FTTP) broadband, which represented a monumental leap forward from the aging and ailing national internet infrastructure reliant on deteriorating copper cabling.

For those not deeply entrenched in the local telecommunications arena, it’s challenging to fully convey the seismic impact of this policy shift.

Previous governments had made attempts, ultimately unsuccessful, to rally the local industry, notably Telstra, into supporting an infrastructure upgrade. What followed was an audacious move that effectively sidelined the nation’s major players.

In a whirlwind timeframe, the government found itself compelled to birth a startup of its own, promptly named NBN Co (with no luxury of time to devise a more elaborate title).

This nascent company embarked on an ambitious mission – to deliver high-speed connections directly to the homes of 93 percent of households.

For the remaining segments of the population, satellite and fixed wireless technologies would assume the role of connectivity providers, signaling the end of the copper era.

Fast forward eleven years, and history seems poised to repeat itself, albeit with a different political backdrop. The opposing political faction, having spent seven years in governance reshaping and reimagining the NBN through alternative, lower-quality means, then unveiled a substantial $4.5 billion initiative.

The new endeavor aimed to usher in FTTP (Fibre to the Premises) technology and ultimately realise the vision originally conceived by Rudd and Conroy.

The original NBN venture represented a colossal undertaking, one that garnered broad public support despite an aggressive campaign waged by the opposition Coalition and certain segments of the media, painting the concept as an extravagant overreach and a monumental fiscal squander.

It was far from a budget-friendly endeavor. During the period in which it sought the favor of local telecommunications companies, the initial blueprint envisioned a privately-led joint venture powered by $4.7 billion in taxpayer funds.

The scheme aimed to construct a Fibre to the Node (FTTN) network, serving a remarkable 98 percent of premises. FTTN technology entailed the deployment of fiber cabling up to street corners, with existing copper infrastructure responsible for the last leg of the internet journey to homes.

At the time, Labor’s plan bore an estimated cost of $43 billion, and the assurance of generating a commercial return was integral to preventing it from impacting the national budget’s bottom line.

While the wisdom of committing such substantial public funding to a scheme that eluded the comprehension of most Australians was a subject of heated debate, its role as a political football was solidified during the 2010 federal election, where it arguably played a pivotal role in maintaining Labor’s hold on power.

During the election, the Coalition, led by opposition communications spokesman Tony Smith, put forth a broadband policy that was notably underfunded, allocating a mere $6 billion to the cause.

Their proposal also included the dissolution of NBN Co and the sale of its existing infrastructure to commercial operators.

Labeling the FTTP NBN as an extravagant expenditure, the Coalition vowed to terminate its deployment and instead focus on establishing metropolitan and regional wireless networks, all while upgrading underperforming copper networks.

Andrew Robb, the Coalition’s finance spokesman at the time, asserted that Labor was squandering tens of billions of dollars by putting all its chips on a single technology. He said, “the private sector is quite capable of identifying where there is a demand for fiber to the home.”

The outcome of the election yielded a hung Parliament, with independent MPs Rob Oakeshott and Tony Windsor throwing their support behind Labor. They cited Labor’s superior broadband policy as a decisive factor influencing their decision.

$3.5 Billion Investment A Waste Of Money

The notable policy transformation that would define the majority of the eventual NBN rollout took its initial steps when Malcolm Turnbull assumed the role of opposition communications spokesman in 2013.

His mission was to redirect the discourse and attempt to defuse a policy that had proven to be a political boon for Labor.

Upon his appointment to the position, Turnbull remarked, “The fundamental problem is that there is no transparency here – the government has asserted, but not proven, that the $43 billion investment is going to result in an asset worth $43 billion. All the evidence shows it will result in an asset worth considerably less. That’s a huge destruction in value.”

Having easily outmaneuvered Tony Smith in broadband policy debates, Stephen Conroy encountered a formidable adversary in Turnbull.

Turnbull possessed the ability to present a seemingly compelling case on television for a substantial policy shift, even to an audience with minimal opportunity to grasp the nuances between FTTP and FTTN in a brief five-minute segment.

The significant policy pivot gained momentum following the Coalition’s resounding victory in the 2013 federal election.

Turnbull argued that delays in the rollout under Labor had led to a mere 51,000 premises being connected. Instead of committing to rectify the challenges faced by the troubled FTTP rollout, the Coalition opted for a far-reaching “multi-technology mix” proposal for the election.

For under $30 billion, Turnbull also promised to repurpose some of the previously discarded copper networks in a network using a vast majority of FTTN to provide everyone with minimum download speeds of 25 megabits per second by 2016, and then 50 Mbps by 2019.

“It’s all very well for Labor to talk about very fast broadband but they are failing to deliver it,” Turnbull said at the policy’s launch.

“This [multi-tech policy] will deliver speeds that are more than capable of delivering all of the services and applications households need … Speed is only valuable to you in so far as you can use it for something.”

When pressed by journalists regarding the durability of the copper networks he was intent on preserving, Turnbull offered evasive responses, emphasising potential future enhancements such as vectoring to improve the longevity of copper infrastructure.

Before he could potentially face termination, Mike Quigley resigned from his position. Subsequently, following the election, Bill Morrow assumed the role of the new CEO tasked with reshaping the NBN and pursuing an alternative direction.

However, by December of that same year, the first signs of trouble emerged when the MTM (Multi-Technology Mix) plan had to undergo significant recalculations.

NBN Co’s then freshly appointed board conducted a strategic review that, amid controversy, concluded that Labor’s original plan would have taken three additional years to complete compared to earlier estimates and would cost an additional $29 billion, bringing the total expenditure to $73 billion.

This substantial figure was strategically employed to divert attention from the fact that the Coalition’s own plan had now ballooned to a much larger $41 billion, significantly exceeding the $29.5 billion initially pledged before the election.

Since then, the MTM (Multi-Technology Mix) policy has endured, albeit with persistently low public approval. Successive communications ministers, initially Mitch Fifield and now Paul Fletcher, have grappled with the challenging mission of convincing the public of the merits of a network that has left many citizens feeling unimpressed.

Despite the official declaration of completion earlier this year, a substantial segment of the nation remains without internet connectivity. The project’s costs had soared to $51 billion, earning widespread criticism for its lackluster performance.

USA’s Lightning-Fast 10Gbps Internet Speed Plans at Just $49 a Month Leaves Australia In The Slow Lane

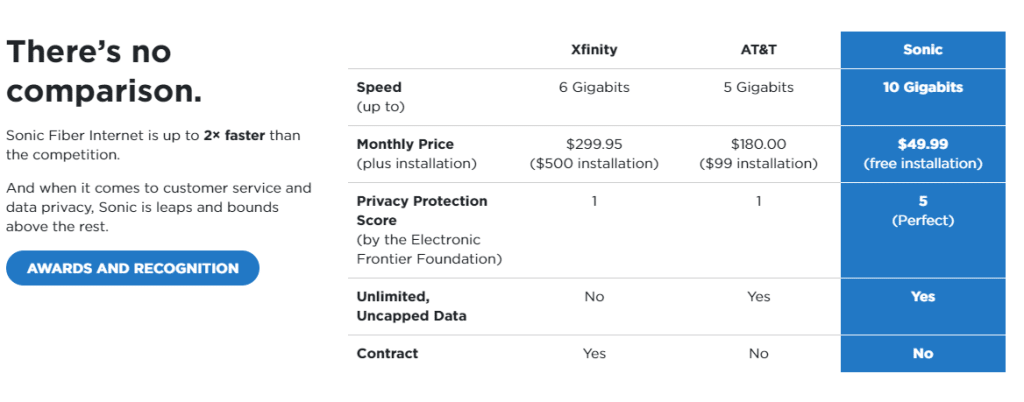

The digital divide between internet speeds and affordability has once again come into sharp focus as the United States rolls out blazing-fast 6Gbps internet plans at an astonishingly low $49 per month.

In stark contrast, Australians continue to grapple with internet speeds that max out at just 50Mbps, all for the hefty price of around $105 per month.

In an era where fast and reliable internet connectivity is no longer a luxury but a necessity for work, education, and entertainment, the discrepancy in both speed and cost is impossible to ignore.

To grasp the magnitude of the difference, let’s put these numbers into perspective. In the United States, for just $49 per month, subscribers can enjoy an astonishing 6Gbps connection.

In summary, for a fraction of the cost, residents in the United States can access internet speeds faster than what Australians are offered. The disparity in both performance and affordability raises concerns about Australia’s position in the global digital landscape.

List Of Countries With The Best Internet Speed

The list of countries boasting the highest internet speeds is led by Monaco, followed by Singapore, Chile, Hong Kong, China, Switzerland, France, Denmark, Romania, and Thailand.

Monaco takes the top spot with an impressive average internet speed of 319.59 Mbps, while Singapore secures the second position with an average internet speed of 300.83 Mbps.

Chile clinches the third spot with an average internet speed of 298.5 Mbps, and Hong Kong follows closely as the fourth-fastest in the world, boasting an average internet speed of 292.21 Mbps.

China secures the fifth position with a robust average internet speed of 280.01 Mbps, while Switzerland claims the sixth spot with an average internet speed of 279.8 Mbps.

France ranks seventh with an average internet speed of 271.33 Mbps, while Denmark is close behind at eighth place, boasting an average internet speed of 270.27 Mbps.

Romania secures the ninth position with an average internet speed of 260.97 Mbps, and Thailand rounds out the top ten with an average internet speed of 260.54 Mbps.

1. Monaco – 319.59 Mbps

2. Singapore – 300.83 Mbps

3. Chile – 298.5 Mbps

4. Hong Kong – 292.21 Mbps

5. China – 280.01 Mbps

6. Switzerland – 279.8 Mbps

7. France – 271.33 Mbps

8. Denmark – 270.27 Mbps

9. Romania – 260.97 Mbps

10. Thailand – 260.54 Mbps

The Digital Gulf Widens

As the digital divide continues to widen, Australians find themselves trailing in the wake of countries offering faster and more affordable internet services.

The discrepancy not only affects the quality of life but also has profound implications for education, business competitiveness, and overall economic development.

For now, Australians can only look enviously across the Pacific at the lightning-fast and cost-effective internet plans enjoyed by their American counterparts.